Dividing the project into tasks (aka activities) is the first practical step in project scheduling.

Dividing the project into tasks (aka activities) is the first practical step in project scheduling.

Small projects might have an obvious task breakdown. But we recommend learning this subject anyway because even a small problem with the task list, especially an omission, can be devastating after the project has been estimated and a full schedule produced.

The PMBOK dedicates a process to defining the task activities of the project. It is called Define Activities.

PMBOK, 5th Edition, Section 6.2, “Define Activities”

Define Activities is the process of identifying and documenting the specific actions to be performed to produce the project deliverables. The key benefit of this process is to break down work packages into activities that provide a basis for estimating, scheduling, executing, monitoring and controlling the project work.

The format of the task list is irrelevant, but unless there is a reason to produce something more fancy it should consist of a simple list of tasks.

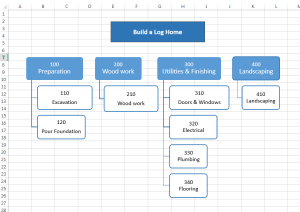

Let’s take our hypothetical log home project from the previous tutorial page. Here’s what the task list might look like.

| Task List | |

|---|---|

| Task ID | Name |

| 110 | Excavation |

| 120 | Pour Foundation |

| 210 | Wood work |

| 310 | Electrical & Plumbing |

| 320 | Flooring |

| 330 | Finishing |

| 410 | Landscaping |

The graphical view helps you visualize it to make sure it’s all there:

At this point the goal is simply to make sure it’s all there. Believe me, if you missed something it will show up later. But here is a checklist which will help you to determine when the task list can be finished decomposition:

- Make sure it can be reliably estimated. The tasks should be broken down to a point where a reliable estimate can be produced. If you are still unsure about the cost and/or duration of the task, consider breaking it down further.

- Base it on Deliverables. Each deliverable should have a clearly defined task, or set of tasks, in place to produce it.

- Have only one Responsible Party. When you have multiple people and/or organizations responsible for the completion of a task, it is difficult to control and manage. In fact, I’ve committed this sin with the task Electrical & Plumbing, but often these are very well understood tasks and not likely to have major fluctuations.

- Match tasks to cost accounts. Maybe your organization has predefined cost accounts, such as “Wood work”, or “Flooring” that should be used.

- Make it measurable. It should be easy to put a percent complete value on a task at any time, but on time (schedule) progress and budget progress. If this is not easy to do, maybe it should be broken down further.

Here are a few experience-proven rules of thumb which can give you a general guide regarding the size of tasks:

- Tasks should be between 8 and 80 man-hours of labor. This is a manageable amount. Any more, and you will lose control of the task because you are trying to manage a major subproject. Any less, and you will lose control of the project by micromanaging tiny tasks. That being said, if you are learning project management it is best to try a small project with small tasks.

- Tasks should not be much longer in duration than the distance between two status points, usually weekly status meetings. When performing earned value analysis during those status points, the percent complete for big tasks inevitably gets assigned as something like 35%, 65% or 95%. This is difficult to control and project team members will exaggerate it. If you create the task to be small enough so that only 0%, 50% or 100% can be used, there can be no guessing as to whether a task is not started, in progress, or complete.

- Any level should contain no more than 10 tasks per phase. This makes the phase manageable and provides valuable reference points.

There is no correct length to a task, and experience is an important factor. But although this may seem like a simple exercise it can make the difference between good project control and feeling out of control.

External Information Sources

If you, or a member of your team, can reliably estimate the work on your own, this is a good situation to be in. But most often some level of extrapolation is needed from other information sources. Three sources that should be considered are:

- Previous Projects. Very few projects are absolutely unique. There are always other projects from which data can be gleaned and task lists appropriated. It’s even better when the project’s issues have been documented, because special attention can be given to tasks by breaking them down.

- Expert Judgment. If you have access to an expert, this is the time to use them. How should the project be divided up? What is the estimated duration? Estimated cost? Required resources? Some of those questions refer to future parts of the schedule development processes, but the activity list is the foundation.

- Templates. Every project should consider activity list templates. If none exist, let it be the first one, and adjust the activity list into a template for use on future projects. In our engineering company, most bridge projects are similar. Sometimes the bridge is across a road, other times a stream. But this does not change the activity list substantially, and we have a standard activity list we pull off the shelf and adjust to fit the situation. It ensures that nothing gets missed. The PMBOK refers to “WBS templates” in developing the WBS, but the same applies for the Activity List.

Sequencing Activities

After the project has been divided into tasks the relationships between them must be determined. Most of the time a task starts when the previous one finishes, but not all the time, so the proper relationship between tasks must be documented in order to fully define the project. The PMBOK has a process called Sequence Activities.

PMBOK, 5th Edition, Section 6.3, “Sequence Activities”

Sequence Activities is the process of identifying and documenting relationships among the project activities. The key benefit of this process is that it defines the logical sequence of work to obtain the greates efficiency given all project constraints.

There are, in fact, four types of dependencies:

- Finish to Start (FS): This is the most common dependency. When tasks A and B have an “FS relationship,” task B cannot start until task A finishes.

- Finish to Finish (FF): When tasks A and B have an FF relationship, task B cannot finish until task A finishes.

- Start to Start (SS): When tasks A and B have an SS relationship, task B cannot start until task A starts.

- Start to Finish (SF): When tasks A and B have an SF relationship, task B cannot finish until task A starts.

On top of this, you can specify an offset from the start or finish point of a task, called a lead or lag.

- Lead: The amount of time whereby a successor activity can be advanced with respect to a predecessor activity. For example, if tasks A and B have an FS relationship with a lead of 5 days, task B cannot start until 5 days after task A has finished.

- Lag: The amount of time whereby a successor activity will be delayed with respect to a predecessor activity. For example, if tasks A and B have an FS relationship with a lag of 5 days, task B cannot start until 5 days before task A has finished.

Leads and lags are the inverse of each other, similar to height and depth. They both have units of time. Most project management software uses only lags, and leads are specified simply as negative lags.

The PMBOK specifies that all tasks require a dependency, and this is technically correct. If a task is not dependent on another within the project, then it can’t be a part of the project. But from a practical perspective, task dependencies will introduce an unnecessary layer of complexity in small projects unless you are using sophisticated project scheduling software. It is possible to simply avoid specifying any dependencies and thereby assume that all dependencies are FS (Finish to Start). In our example that’s exactly what we will do.

In our log home example project, therefore, a column is added to the table from the previous step (task identification), like this.

| Task List | ||

|---|---|---|

| Task ID | Name | Dependencies (FS relationship) |

| 110 | Excavation | |

| 120 | Pour Foundation | 110 |

| 210 | Wood work | 120 |

| 310 | Electrical & Plumbing | 210 |

| 320 | Flooring | 210 |

| 330 | Finishing | 210, 310 |

| 410 | Landscaping | 120 |

Navigation

- Previous Page: Introduction

- Next Page: Estimating Resources

- Home: Project Scheduling Tutorial